I haven’t done an “Arresting Images” post in a while, so it’s about time that I do! “Arresting Images,” just to recap, are words that Shakespeare uses that make you stop and think, “Wow! He just made something so seemingly normal or overdone sound so meaningful, so memorable! That must be why we’re still studying his work after 400 years!”

Carmen Grant as Isabella and Tom Rooney as Angelo in the 2013 Stratford Festival production of Measure for Measure

I recently saw the Stratford Festival’s production of Measure for Measure and it reminded me of all the arresting images that this play has to offer. Although the plot isn’t particularly well-known, you’ve probably seen the metaphors printed on a coffee mug or fridge magnet.

The play is about the nature of justice: when the Duke of Vienna feels like he hasn’t been fulfilling his duty to uphold the law, he takes a short hiatus to wander the streets in costume, putting himself in touch with the voice of the people while the scrupulous Angelo holds down the fort.

When Angelo takes the reigns, people are surprised at his severity. Isabella, a nun-in-training, begs Angelo not to execute her brother for the crime of impregnating his girlfriend, who had enthusiastically consented to the union. The stand-in Duke responds:

“The law hath not been dead, though it hath slept.”

Isn’t that amazing? Angelo is showing that he is waking up the legal system of Vienna. Angelo sees the citizens as assuming that they can get away with breaking the laws (in this case, laws against premarital sex) because the Duke hadn’t enforced them. While Angelo is waking up the legal system, he offers the people of Vienna a harsh wake-up call.

Isabella begs Angelo to forgive her brother’s youthful impetuousness, and says that Claudio will remedy the crime by marrying and taking care of the expectant Juliet (no, not that Juliet). Angelo refuses to yield to this reasonable solution, and offers the most outstanding metaphor as to why it’s necessary for him to start upholding the law:

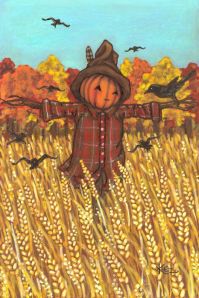

We must not make a scarecrow of the law,

Setting it up to fear the birds of prey,

And let it keep one shape, till custom make it

Their perch and not their terror.

That line is worth reading twice, three times, and then putting it up on a wall somewhere. Instead of saying that “my town, my rules,” Shakespeare provides us with an unforgettable image that even those without farmland can understand: scarecrows are not scary enough. Men with guns are scary, dukes with the power to execute men are scary, but scarecrows are all show, with little power to deter the vultures that might destroy the crops and lead to greater repercussions. Angelo may not be shocked and appalled by Claudio’s engagement in consensual sex, but it’s his job to uphold the law where the Duke was too lenient, and he takes that responsibility seriously.

When discussing the notion of mercy in Shakespeare, people usually refer to Portia’s “The quality of mercy” speech in The Merchant of Venice. Yet, Measure for Measure offers outstanding, and frankly underrated meditations on the nature of mercy, and why sometimes it’s important to allow the legal system some wiggle room in order to let people coexist in peace.

Thematically, this play interrogates whether a binary even exists between justice and mercy, and metaphorically, it offers outstanding imagery of the battle between darkness and light. Lucio is Claudio’s best friend, and his name is derived from Latin words that mean “light” or “shine.” Angelo represents his foil (his character opposite), but instead of being the darkness to snuff out Lucio’s light, he’s the cold that threatens to overcome Lucio’s shining sun of humour and optimism. Lucio calls Angelo

“a man whose blood / Is very snow-broth”

– isn’t that amazing? It gives me the chills just to think about it! I think about the slush that I walk on in the winter, and the countless bowls of soup it takes to warm me up, and that shows me that I would never want to deal with someone so stubborn, so disagreeable, as to be comprised of snow-broth.

So that brings my quick exploration of Measure for Measure’s arresting images to a close. I’m not sure why this play isn’t taught in high schools. It’s got material on teen pregnancy, good quotes for pre-law keeners, and ultimately offers essay topics that are ripe for the picking. Have you tried teaching Measure for Measure in your classroom?